Tuning In

[ Anna Madeleine Raupach ]

On 8th November 2023, equipped with an antenna and laptop, I ride to a nearby field of grass that was once a drive-in cinema and always Ngunnawal Ngambri land. Here, as I have done almost every day since mid-October, I quickly attach the antenna to my bicycle handlebars and plug it into my laptop. Using a software defined radio (SDR) program tuned to 137.62MHz, I connect with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) weather satellite NOAA15 as it broadcasts an Automatic Picture Transmission (APT) signal, receiving its perspective as it imminently passes overhead.

In the software on screen, amid the yellow ‘noise’ dotting a blue background, a series of parallel lines emerge along with a rhythmic beep that gradually strengthens to a ticking, chirping sound. This electric pulse has come to signify a familiar sense of connection, much like the dial-up modem call of early internet days. But rather than to humans via chat, this transmission connects me to a computer that encircles the globe witnessing Earth, sea and sky—and what we have done to them—as it has done several times a day for the last 25 years. My fleeting encounter with NOAA15 allows me to record its signal as an audio file that I decode to reveal an image. I have repeated and refined this process over the past year. The latest evolution is the ‘bike-tenna’ which allows me a quick escape from the multitude of devices whose invisible radio interference fills our homes and suburbs.

Bike-tenna set up, Ngunnawal Ngambri Country, 2023.

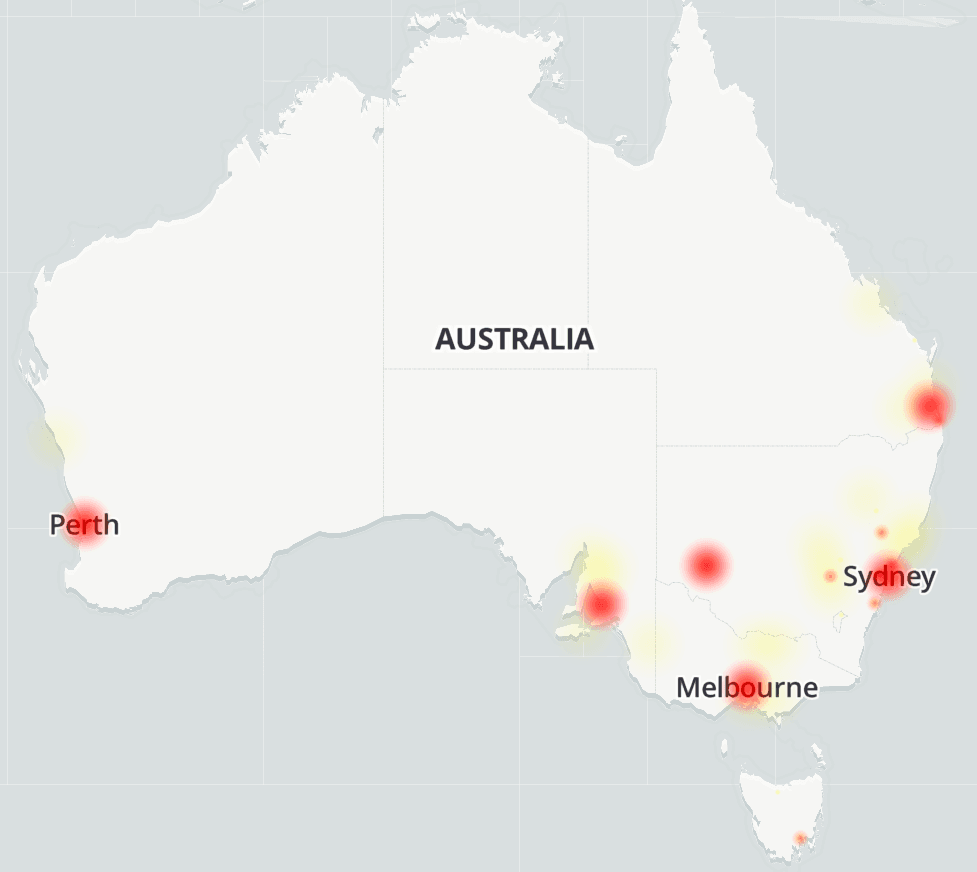

That day, the radio landscape was clear. I also noticed my own 4G network was down, but it was only after returning home I learnt that one of Australia’s largest network providers Optus had suffered a nation-wide outage which continued to significantly impact businesses, transport and healthcare for the rest of the day. Mapped on Downdetector, a user driven platform for monitoring network disruptions, the Optus outage emerged as a series of unintentional holes in our ubiquitous connectivity, an inversion of ‘radio quiet zones’ from remote locations to city centres.

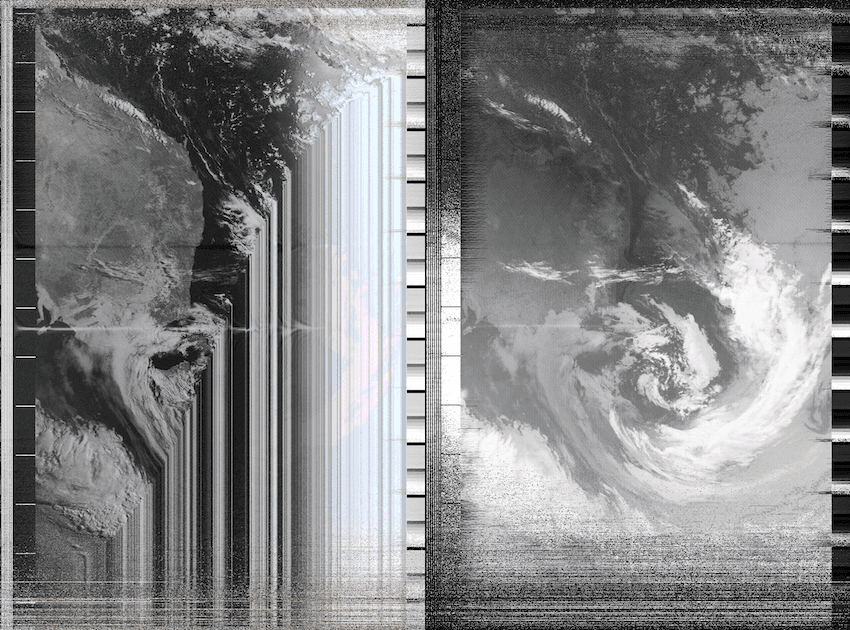

Satellite image received from NOAA15, 23rd October 2023.

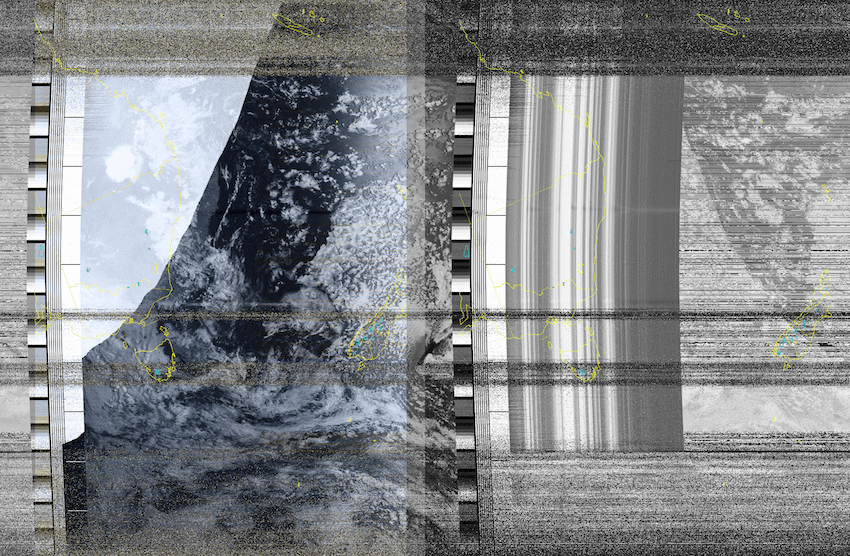

This confluence of a technological fault and experimental artistic practice illuminates a set of questions about our modern atmosphere. Without scientific knowledge of meteorology, I read the satellite images I receive through a different visual language. My attention to NOAA15 has been piqued since becoming aware that a damaged satellite sensor is causing degraded data that alters the image composition. Rather than clearly defined, the pixels of land, sea and sky are fractured and sliced, bleeding through the picture plane, and framed by grey static that marks the moments the satellite dips above and below my visible horizons. In addition to meteorological information, the image expands to convey interactions between socio-technical actors on a planetary scale: a faulty US government satellite in dialogue with the social structures that allow me access to a laptop, software, antenna, knowledge and an open field.

Downdetector visualisation of Optus outage, 8th November 2023.

The research that led to my daily bike-tenna ritual explores human interference in outer space with a focus on satellite mega-constellations. While separate from these vast networks, NOAA satellites are distinct because their signals are open access, unlike those owned by private companies. Sputnik also shared this quality that supports the values of a global commons rather than a privatised, militarised, orbital space. Treating lower Earth orbit in this way provides access not only to signals, data and images, but generates a community. Leading this movement is Open-weather, led by artist duo Sophie Dyer and Sasha Engelmann, whose Nowcast (2020) project creates a composite set of NOAA images received from participants around the world accompanied by an archive of field notes recording local observations of climate change.

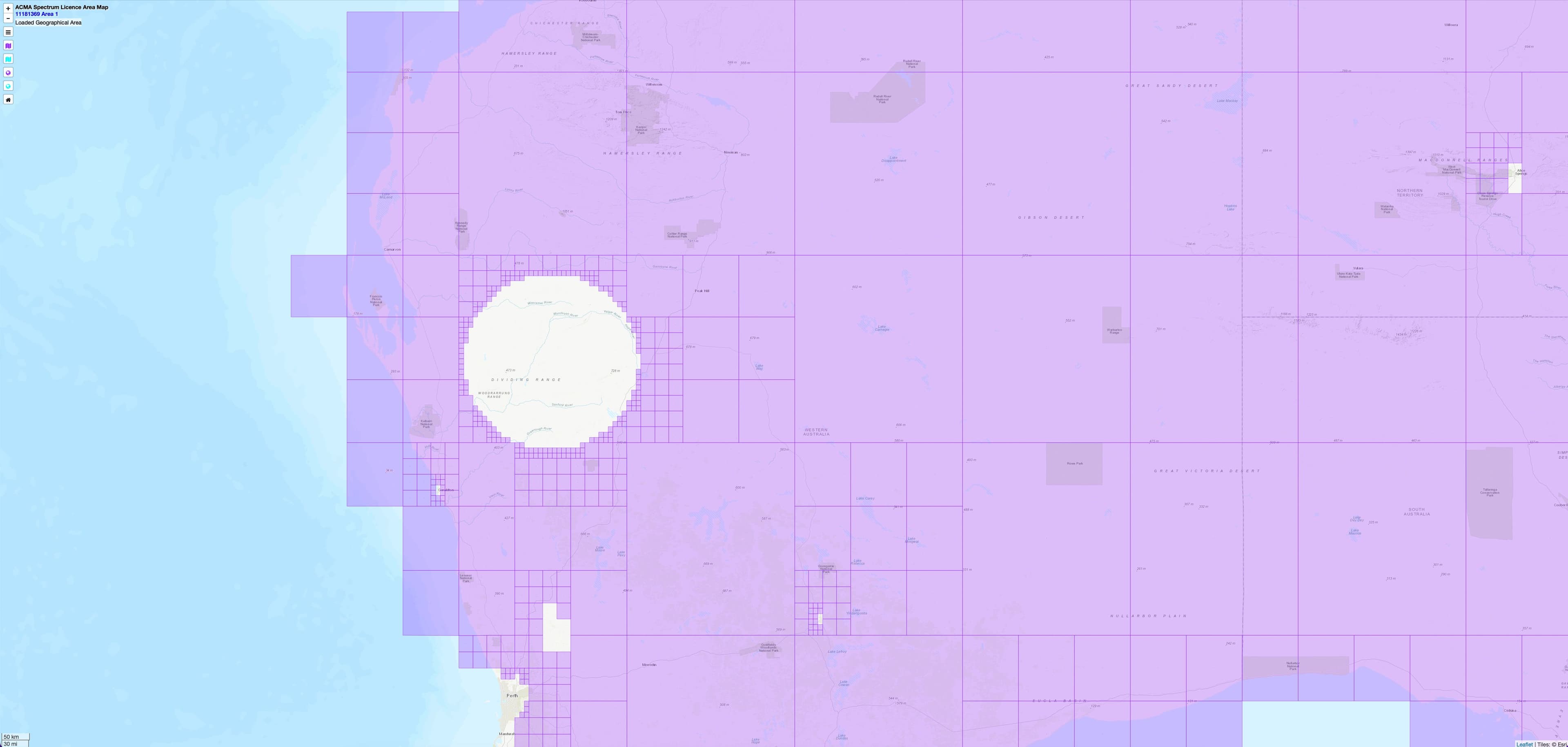

Australian Communications and Media Authority Spectrum License Area Map showing radio quiet zones around the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) Radio Observatory site in Western Australia and around Pine Gap, Alice Springs.

Satellite image received from NOAA15, 8th November 2023.

Empowering people to independently conjure a satellite perspective bypasses the weather channels we normally consult to gauge the atmosphere and creates a ‘counter-image’ that shifts satellite imagery from a scientific to social domain. A distilled relationship between an individual and satellite traverses the bodies, buildings, devices, transport systems and infrastructures influencing the atmosphere that mediates the Earth image. Echoing the more-than-human, Dyer and Englemann borrow from geography fields the term “more-than-meteorological” to “figure the weather as sociopolitical and cultural as well as atmospheric”. Here, what would be ‘noise’ in the science of meteorology can be co-opted to tell diverse stories of place and its inhabitants.

The evolution of computing and meteorology are inextricably linked and enfolded in military history. In 1922 experimental physicist Lewis Fry Richardson pioneered algorithmic weather prediction and envisioned human computers in a ‘Forecast Factory’ calculating the weather for assigned parts of the globe. A transmission of image to antenna echoes this direct relationship between humans and their immediate weather. But scaled up and commercialised, the wires become crossed: rich countries pollute the atmosphere for vulnerable nations, and access to technology and the impacts of it on the environment are unequally distributed and unevenly governed.

During my 10-minute intervals in the field as a satellite passes overhead, I read about Gaza and contemplate all that NOAA15 sees in its 102-minute journey around the Earth. For Richardson, who was a Quaker and conscientious objector, the military applications of meteorological work were a moral dilemma and led him to contribute to peace research by applying mathematical prediction to the frequency of war. One area of investigation included the role of geography in both weather and conflict, where land and borders delineate movement of social and environmental forces across land, sea and sky. As orbital space resists geographical borders, its power dynamics are reconfigured in other ways, for example as private aerospace company SpaceX gains control of crucial network connectivity in warzones.

Perhaps a satellite reflects not only sunlight, but a glimpse of the cumulative words and actions we have added to Charles Babbage’s vast library of air. From this expanse, what does it mean to receive a tangible analogue radio signal that reveals a broken image of the world? Here, an alternative view of how humans ‘compute’ the weather can be found: one that is intrinsic to the intimate, local and community stories imprinted in our noisy, crowded, contested atmosphere.

Notes

Anna Madeleine Raupach, “ANAT Synapse Residency Creative Research Journal”, accessed 19 November 2023, http://raupach2022.blog.anat.org.au/.

Sasha Engellmann and Sophie Dyer, “Open-weather”, accessed 18 November 2023, https://open-weather.community/.

Sasha Engellmann, Sophie Dyer, Lizzie Malcolm, and Daniel Powers. "Open-weather: Speculative-feminist propositions for planetary images in an era of climate crisis." Geoforum 137 (2022): 237–247

Open-weather, “Feminist open-weather handbook”, accessed 18 November 2023, https://open-weather.community/feminist-handbook/; Astrida Neimanis and Jennifer Mae Hamilton. "Open space weathering." Feminist Review 118, no. 1 (2018): 80–84.

Peter Lynch. "Richardson's Forecast: the Dream and the Fantasy." arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.01674 (2022).

Nils Petter Gleditsch. Lewis Fry Richardson: His intellectual legacy and influence in the social sciences. Springer Nature, 2020.

The New York Times, “Elon Musk Acknowledges Withholding Satellite Service to Thwart Ukrainian Attack”, accessed 20 November 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/08/world/europe/elon-musk-starlink-ukraine.html.

Artist & Lecturer

Anna Madeleine Raupach

Dr Anna Madeleine Raupach is a multidisciplinary artist based on Ngunnawal and Ngambri land, and a Lecturer at the ANU School of Art & Design. Her practice engages with science and technology to address socio-political issues enmeshed with climate change. Anna has a PhD in Media Arts from UNSW Art & Design (2014), a Bachelor of Visual Arts (Honours) from ANU School of Art & Design (2007), and in 2024 is a Fulbright Scholar at the University of Southern California’s Expanded Animation program. Recent projects include an ANAT Synapse Residency (2022) and a Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences research fellowship (2019–2020). She has had solo exhibitions in New York, Melbourne, Sydney, Canberra and Bandung, and has been awarded international residencies at the Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris, through the Art Gallery of NSW (2018); and Common Room Network Foundation, Indonesia, with Asialink Arts.